Ecology, evolution, and natural hosts of viruses

1. Ecology of filoviruses

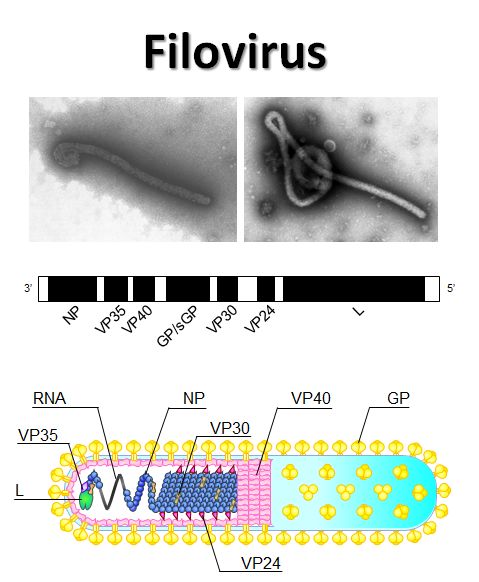

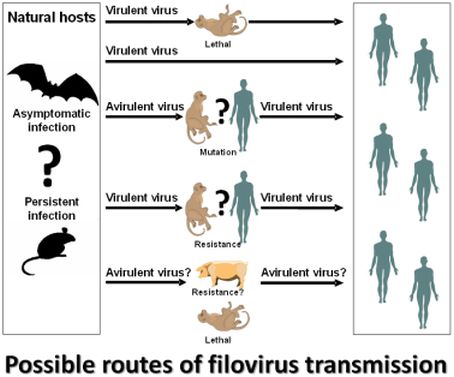

Filoviruses (Ebola and Marburg viruses) cause severe hemorrhagic fever in humans and nonhuman primates. Although fruit bats are suspected to be a natural reservoir of filoviruses. Current findings on the ecology of filoviruses (i.e., natural infection of nonprimate animals and discovery of a new member of filoviruses in Europe) have provided new insights into the epidemiology of Ebola and Marburg hemorrhagic fever. We have started epidemiological studies of filoviruses for wild animals (e.g., fruit bats, nonhuman primates etc.) in Asian and African countries.

Serum samples collected from 353 healthy Bornean orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus) in Kalimantan Island, Indonesia, during the period from December 2005 to December 2006 were screened for filovirus-specific IgG antibodies using the ELISA with recombinant GP antigens. We found that 18.4% (65/353) and 1.7% (6/353) of the samples were seropositive for EBOV and MARV, respectively, with little cross-reactivity among EBOV and MARV antigens. Interestingly, while the specificity for Reston virus, which has been recognized as an Asian filovirus, was the highest in only 1.4% (5/353) of the serum samples, the majority of EBOV-positive sera showed specificity to Zaire, Sudan, Cote d'Ivoire, or Bundibugyo viruses, all of which have been found so far only in Africa. These results suggest the existence of multiple species of filoviruses or unknown filovirus-related viruses in Indonesia, some of which are serologically similar to African EBOVs, and transmission of the viruses from yet unidentified reservoir hosts into the orangutan populations.

Seroepidemiological studies on filovirus infection of nonhuman primates (NHPs) were also conducted in Zambia where Filovirus diseases have never been reported. We screened two NHP species, wild baboons and vervet monkeys captured in Zambia, for their serum IgG antibodies specific to the envelope glycoproteins of filoviruses. From 243 samples tested, 39 NHPs (16%) were found to be seropositive either for ebolaviruses or marburgviruses Interestingly, antibodies reactive to Reston virus, which is found only in Asia, were detected in both NHP species. These results suggest that wild NHPs in Zambia might be nonlethally exposed to these filoviruses.

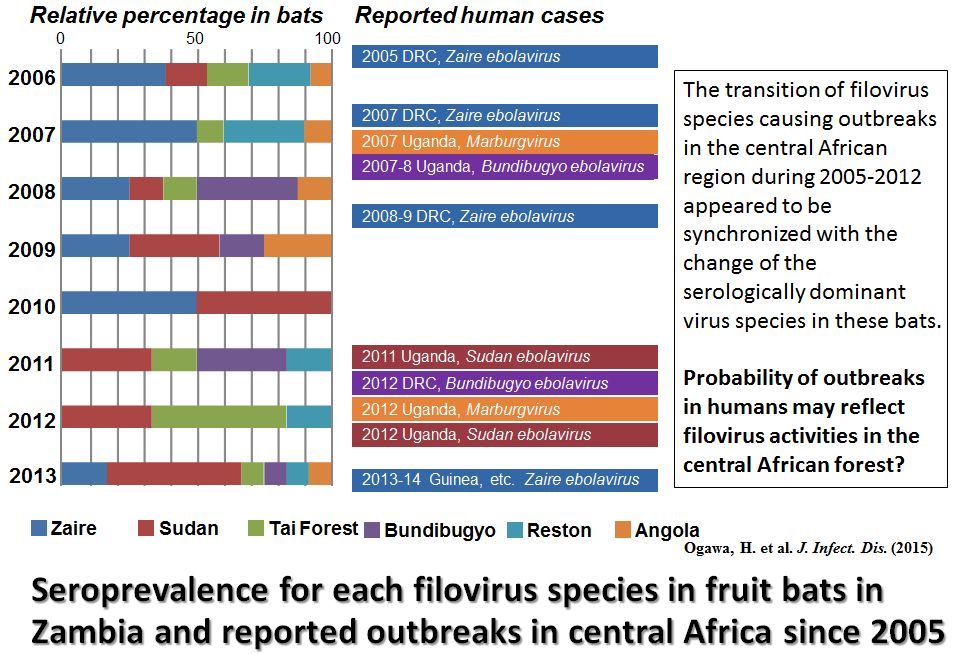

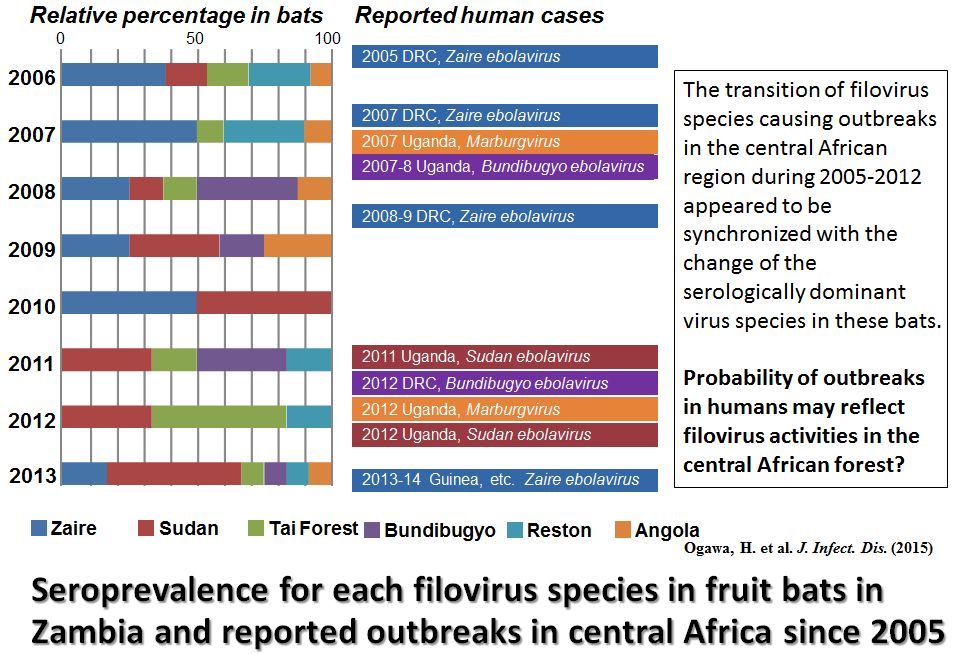

In Zambia, we collect samples also from bats for filovirus research. We detected filovirus-specific immunoglobulin G antibodies in 71 of 748 serum samples collected from migratory fruit bats (Eidolon helvum) in Zambia during 2006-2013. Though antibodies to African filoviruses (e.g., Zaire ebolavirus) were most prevalent, some of the sera showed distinct specificity for Reston ebolavirus, which that has thus far been found only in Asia. Interestingly, the transition of filovirus species causing outbreaks in Central and West Africa during 2005-2014 appeared to be synchronized with the change of the serologically dominant virus species in these bats.

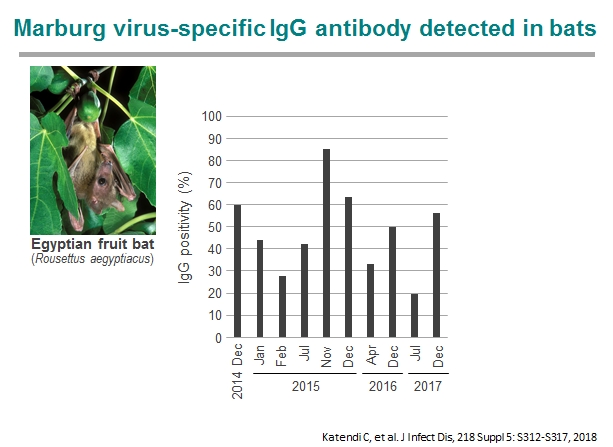

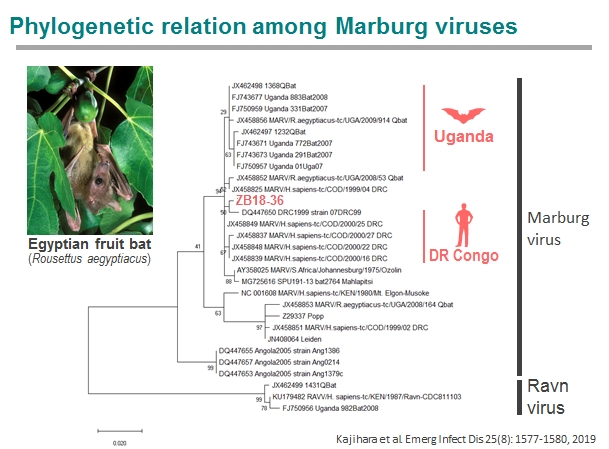

In 2014-2017, we captured cave-dwelling Egyptian fruit bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus) in Zambia and detected IgG antibodies specific to multiple filoviruses in 158 of 290 serum samples of the bats. In particular, most of them were seropositive to Marburgvirus. Interestingly, distinct peaks of seropositive rates were repeatedly observed at the beginning of rainy seasons, suggesting seasonality of the presence of newly infected individuals in this bat population. The seroprevalence was lowest in the bats with body weights ranging from 51 to 60 g and gradually increased as they grew, which likely reflects the disappearance of their maternal antibodies and subsequent infection of young bats. Furthermore, the marburgvirus genome was detected in Egyptian fruit bats captured in Zambia 2018. The virus was phylogenetically closely related to the viruses that previously caused outbreaks in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. These findings suggest that marburgviruses may be maintained by Egyptian fruit bats distributed in sub-Saharan Africa, including the countries previously known to be non-endemic for Marburg disease.

Taken all together. these data suggest the introduction of multiple species of filoviruses in the bat population and highlight the need for continued surveillance of filovirus infection of wild animals in sub-Saharan Africa, including hitherto nonendemic countries.

2. Surveillance of avian influenza in wild migratory birds

Influenza A viruses of 16 hemagglutinin (HA; H1-H16) and 9 neuraminidase (NA; N1-N9) subtypes are maintained in aquatic birds. Of these, H1N1, H2N2, and H3N2 viruses caused pandemics in humans in the last century, whereas direct avian-to-human transmission of H5N1, H7N7, and H9N2 avian influenza viruses has been frequently reported with a public health concern that a new global pandemic could be caused by these avian-derived viruses, which are antigenically different from the H1, H2, and H3 subtypes. We are conducting continued surveillance of these avian influenza viruses in wild aquatic birds bin Japan, Mongolia, and Zambia.

Although the quest to clarify the role of wild birds in the spread of the highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza virus (AIV) has yielded considerable data on AIVs in wild birds worldwide, information regarding the ecology and epidemiology of AIVs in African wild birds is still very limited. During AIV surveillance in Zambia, viruses of distinct subtypes (H3N8, H4N6, H6N2, H9N1, H11N9, and so on) were isolated from wild waterfowls. While some genes were closely related to those of AIVs isolated from wild and domestic birds in South Africa, intimating the possible AIV exchange between wild birds and poultry in southern Africa, some gene segments were closely related to those of AIVs isolated in Europe and Asia, thus confirming the interregional AIV gene flow among these continents.

Please see the Web site below.

Graduate School of Veterinary Medicine Laboratory of

Microbiology, Hokkaido University